During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church permitted Scripture to be used only in Latin and restricted vernacular translations. In the sixteenth century, William Tyndale famously declared, “If God spare my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.” True to his vow, Tyndale undertook the translation of the Bible into English directly from the original Greek and Hebrew, thereby making Scripture accessible to ordinary readers in their own language.

Today, the KJV’s archaic language and numerous “false friends” render it virtually impossible for the average modern reader to fully understand the text they are encountering. Surely, this outcome would have disappointed Tyndale.

One reason many continue to use the KJV is the belief that it constitutes a perfect and inspired translation—a view often associated with “Ruckmanism.” The present article examines and critically evaluates such claims.

Is Textual Criticism Evil?

Do you believe the KJV translators regarded their own work as inspired?

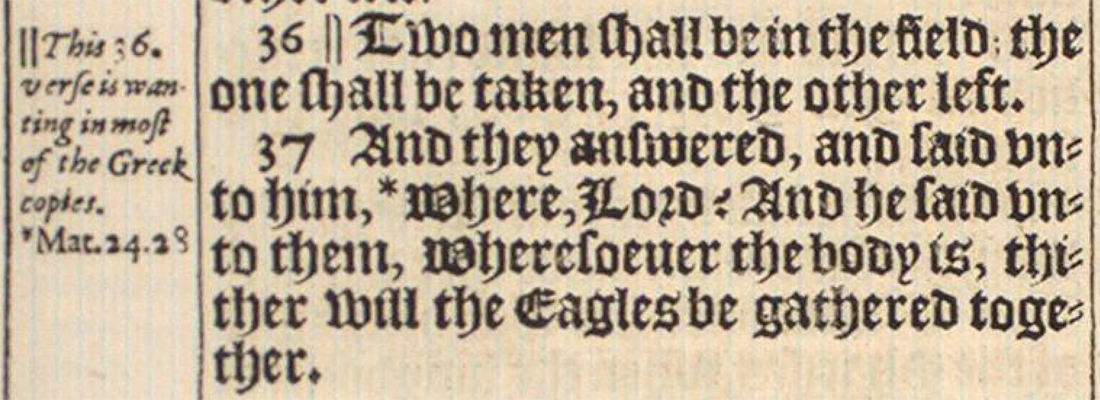

If yes, how do you account for their numerous text-critical marginal notes, which openly acknowledge variant readings and uncertainties in the manuscript tradition?

Would that not entail, by extension, that the text-critical notes themselves are inspired?

If no, what leads you to belive the KJV was inspired?

KJV proponents who argue that textual criticism is inherently “evil” often overlook the fact that the KJV translators themselves engaged in textual criticism and even documented significant textual variants in their marginal notes. A clear example appears in Luke 17:36, where the 1611 edition includes the following note: “This 36. verse is wanting (i.e., lacking) in most of the Greek copies.” Below is an image of this verse as it appeared in the original 1611 KJV:

The 1611 KJV has been digitized and is publicly available on Archive.org

The 1611 KJV has been digitized and is publicly available on Archive.org (see PDF p. 308).

The INTF shows that there are 2,089 manuscripts which contain Luke. (

See INTF List) Of these, only a small number of Greek manuscripts contain Luke 17:36. These include family 13, GA 05 (D), 124, 700, 579, and 1346.

The Error in Hebrews 4:8

The KJV renders Hebrews 4:8 as, "For if Jesus had given them rest, then would he not afterward have spoken of another day." But if Jesus didn't give us rest, who did? Is there a contradiction in the Bible? No, but there is an error in the KJV. It should say, "if Joshua had given them rest."

This is not a textual problem; all extant Greek manuscripts—including those underlying the Textus Receptus—read Jesus (Ἰησοῦς, Iēsous), and the Latin likewise has Iesus.

This example raises a broader question: if the KJV contains even a single error, on what basis can one assert that it is “perfect” or “inspired”?

Literal Translation

If someone desires a literal translation, they would reasonably expect it to approximate the word count of the original text as closely as possible. Daniel Wallace observes that the Greek New Testament contains fewer than 140,000 words, whereas the KJV New Testament contains 180,565 words. By contrast, the RSV, NIV, and ESV all come in at fewer than 176,000 words (

See Wallace's article). This means that the KJV exceeds these translations by more than 4,000 words—and exceeds the Greek text by over 40,000. Why such a significant expansion? If the KJV were truly the most “literal” English translation, should it not, if anything, contain less words than other translations rather than more?

Bill Mounce—Bible translator and author of Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, the best-selling Greek grammar ever published—repeatedly emphasizes a consistent theme across his videos and blog posts: a fully literal translation is impossible. No translation can reproduce every nuance of the source language without loss or distortion, and this limitation is especially pronounced when moving from Greek to English. The structural, lexical, and idiomatic differences between the two languages ensure that some degree of interpretation is unavoidable in every translation.

A clear illustration of this issue appears in the KJV translation of Romans 6:15, where the Greek expression

mē genoito (μὴ γένοιτο) is rendered as “God forbid.” By contrast, the NKJV translates the phrase as “Certainly not!,” as do virtually all modern English versions. Should this divergence be regarded as a sinister corruption of Scripture?

Mē genoito (“God forbid”)!

The passage contains no occurrence of the word God (θεός,

Theos) in any Greek or Latin manuscript. One can verify this easily by consulting a

Greek parallel Bible or any critical edition: not a single textual tradition includes theos here. So why does the KJV insert “God”? Simply because the KJV translators were employing a dynamic equivalent rendering to convey the strength of Paul’s emphatic denial. Modern translations, by contrast, tend to preserve the more literal sense of the Greek expression. This raises an uncomfortable question for KJV-only advocates: if modern translations are condemned as corrupt for occasionally using dynamic equivalence, why is the KJV—which does precisely the same thing—exempt from criticism? Such inconsistency borders on the Pharisaic.

In a previous

blog post on Matthew 5:28, I noted that it is impossible to translate the verse into English while fully preserving the nuances of what Jesus actually said. This difficulty has nothing to do with textual variants; it remains true whether one uses the Textus Receptus or the Critical Text. The linguistic gap between Greek and English simply prevents a perfect, one-to-one rendering. Consequently, if one were to claim that the KJV is inspired and perfect, that assertion would paradoxically imply that the Greek—the very language in which the New Testament was originally written—cannot itself be inspired and perfect.

Bill Mounce offers several incisive observations on the limitations of so-called “literal” translation, both on his

YouTube channel and in

his blog.

Interestingly, the translators of the 1611 King James Bible themselves acknowledged the very same point I am making. In the "Translators to the Reader" section to the original KJV, they explicitly state that their work is not a rigid, word-for-word rendering of the Greek and Hebrew. Rather, their approach aligns more closely with what we would today call dynamic equivalence. As the translators explain:

An other thing we thinke good to admonish thee of (gentle Reader) that wee have not tyed our selves to an uniformitie of phrasing, or to an identitie of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe, that some learned men some where, have beene as exact as they could that way. Truly, that we might not varie from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there bee some wordes that bee not of the same sense every where) we were especially carefull, and made a conscience, according to our duetie.

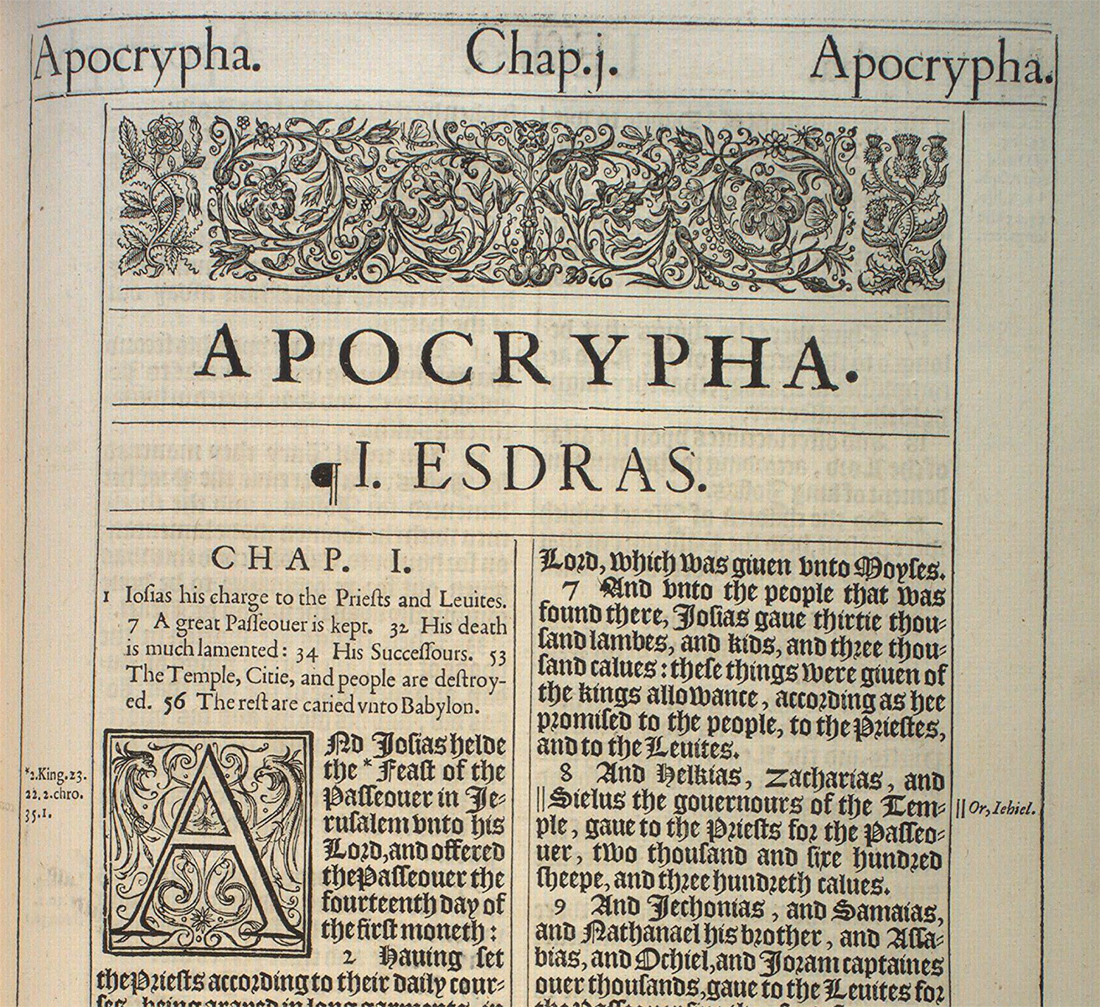

Apocrypha

Did you know that the original 1611 edition of the King James Version included the Apocrypha? It certainly did—and, contrary to some later claims, the translators offered no disclaimer indicating that these books were not to be regarded as Scripture. This can be verified directly:

1611 KJV on Archive.org (see PDF p. 1007).

KJV-only advocate Peter Ruckman insisted that the translators of 1611 never thought for a minute that even one book of the Apocrypha was part of the Holy Bible. They placed the Apocrypha between the Testaments merely as “recommended reading.”

1

Yet nothing in the 1611 preface, The Translators to the Reader, or in the Apocrypha section itself states—or even implies—any such distinction. The opening page of the Apocrypha, reproduced below, contains no indication whatsoever that these books were considered non-canonical by the translators.

Do KJV-only pastors encourage their congregations to read the Apocrypha? If not, why? If inclusion of these books was acceptable to the very translators they regard as inspired, why would it not be acceptable for readers today? Of course, I pose these questions facetiously.

Latin Vulgate Influence on the KJV

In the course of examining divergences between the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) and the Greek Septuagint (LXX), I have observed that the translators of the King James Bible did not consistently adhere to the Hebrew tradition. In several instances, their renderings align more closely with the Latin Vulgate or, at times, with the LXX. As Daniel Wallace has noted, “The 47 scholars who worked on the KJV knew Latin better than they knew Greek or Hebrew. Hence, it should not surprise us that they committed hundreds of errors in translation.” (Source

BiblicalTraining.org)

I previously wrote an

article on 1 Corinthians 13:3, noting that the KJV inserts the phrase “to feed the poor,” a rendering found in no Greek manuscript but derived instead from the Latin Vulgate.

Another example concerns the rendering of the Hebrew term

kûšî (“Cushite”). In 2 Sam 18:21, 22, 23, 31, and 32, the Vulgate reads

Chusi, and the KJV correspondingly translates the term as “Cushi.” This agreement with the Vulgate suggests that the KJV translators prioritized the Latin witness in these verses. By contrast, the HCSB consistently follows the Masoretic Text and translates

kûšî according to its Hebrew sense (“Cushite”/“Cushites”).

A similar pattern appears in 2 Chr 12:3; 14:9, 12–13; 16:8; 21:16; Jer 13:23; 38:7, 10, 12; 39:16; Dan 11:43; and Zeph 2:12. In these passages the Vulgate employs forms of

Aethiops (e.g.,

Aethiops,

Aethiopes,

Aethiopibus), and the KJV follows suit, rendering the term as “Ethiopian” or “Ethiopians.” This departs from the underlying Hebrew

kûšî, which the HCSB consistently translates as “Cushite” in accordance with the Masoretic Text.

Taken together, this data suggests that the KJV frequently preferred the Latin Vulgate as a primary reference point, with the Hebrew and Greek sources functioning in a secondary or mediating role. This dependence on the Vulgate highlights a significant limitation in the KJV translation process and underscores the need for modern translations that more accurately reflect the original languages.

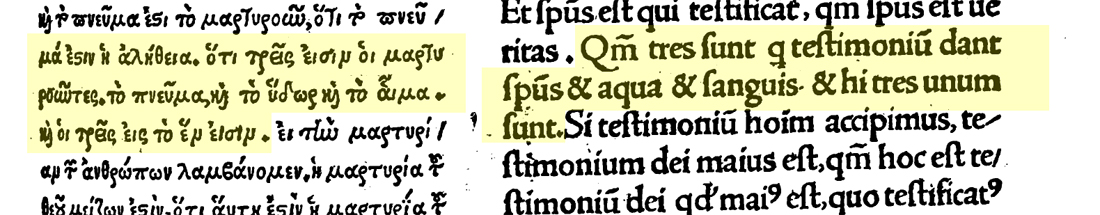

The Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7-8)

For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one. (1 John 5:7-8 KJV)

For there are three that testify: the Spirit and the water and the blood; and the three are in agreement. (1 John 5:7-8, NASB)

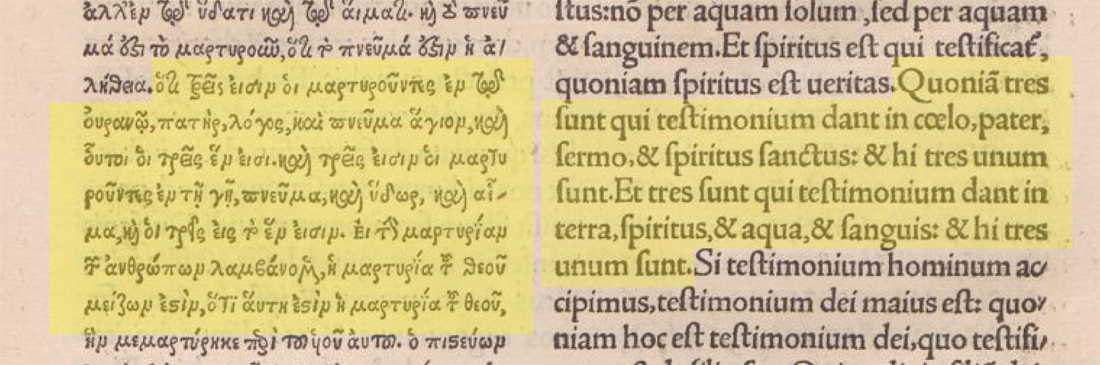

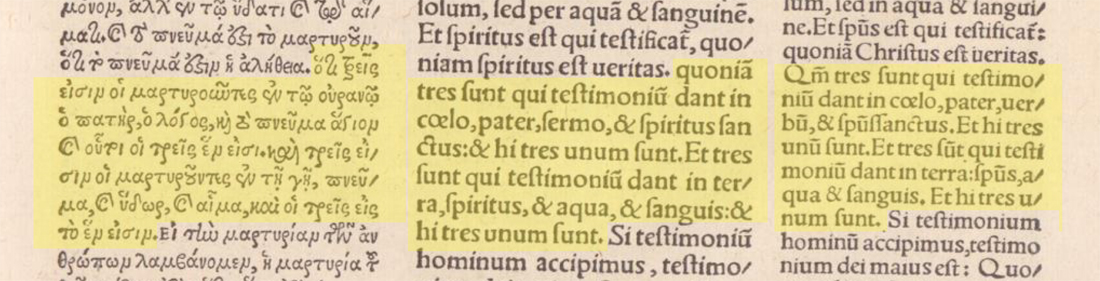

This passage appears quite differently in modern translations, leading some KJV proponents to allege that contemporary versions have “removed” a clear reference to the Trinity from the biblical text. The KJV’s reading derives from Erasmus’s Greek text, which—prior to later revisions—agreed with the form preserved in both the Greek and Latin manuscripts underlying modern translations. Under significant pressure, Erasmus ultimately altered his text, and the effects of these changes can be clearly observed in the comparison below.

Erasmus's 1st Edition (1516) The original edition is accessible via Archive.org.

Erasmus's 1st Edition (1516) The original edition is accessible via Archive.org.

Erasmus's 3rd Edition (1522) The original edition is accessible via Archive.org.

Erasmus's 3rd Edition (1522) The original edition is accessible via Archive.org.

Erasmus's 4th Edition (1527) The original edition is accessible via Archive.org.

Erasmus's 4th Edition (1527) The original edition is accessible via Archive.org.

The INTF shows that 460 Greek manuscripts contain 1 John (See INTF List). Elijah Hixson states, "There are 10 Greek manuscripts that have the CJ, but only three of them have it in the same form as in Stephanus’ 1550 edition and Scrivener’s edition reprinted by the TBS—these three are 221marg, 2318 and 2473. (see article

Hixson, in the same article, provides a list of the manuscripts that contain this reading:

- GA 629 (c. 1362–1363 AD). This was a Latin-Greek diglot.

- GA 61 (prob. c. 1495–1521 AD)

- GA 429marg (date: after 1522). The manuscript itself dates to the fourteenth century; however, the marginal addition was made by a later corrector sometime after 1522.

- GA 918 (prob. c. 1573–1578 AD)

- GA 2473 (c. 1634 AD)

- GA 2318 (c. 1700s AD)

- GA 177marg (c. 1785 AD). The manuscript itself dates to the eleventh century, but the addition of the Comma Johanneum was made much later—in 1785—and even includes a verse number supplied by the corrector.

- GA 221marg (after c. 1850?). It is a tenth-century manuscript, with the verse added later as a marginal annotation. Henry Coxe’s catalogue of manuscripts printed in 1854 explicitly states that this manuscript lacks 1 John 5:7.

- GA 88marg (?). The manuscript itself dates to the twelfth century, though the marginal addition is of much later origin.

- GA 636marg (?). The manuscript dates to the fifteenth century; however, the Comma Johanneum appears to have been added by a later hand.

It is likewise absent from the earliest Latin manuscripts. Both Codex Fuldensis (6th century) and Codex Amiatinus (8th century) omit the Comma Johanneum.

KJV Changes 1611 vs. 1769

Editions

Joshua 3:11

1611 has "even" (euen) and the 1769 has "of."

"Arke of the Couenant, euen the Lord" (1611) View online

"ark of the covenant of the Lord" (1769) View online

2 Kings 11:10

The 1611 lacks "of the LORD."

"in the Temple" (1611) View online

"in the temple of the LORD" (1769) View online

Isaiah 49:13

"for God" (1611) View online

"for the LORD" (1769) View online

Jeremiah 31:14

"with goodnesse" (1611) View online

"with my goodness" (1769) View online

Jeremiah 51:30

"burnt their dwelling places" (1611) View online

"burned her dwellingplaces" (1769) View online

Ezekiel 6:8

"burnt their dwelling places" (1611) View online

"burned her dwellingplaces" (1769) View online

Ezekiel 24:5

"let him seethe" (1611) View online

"let them seethe" (1769) View online

Ezekiel 24:7

"powred it vpon the ground" (1611) View online

"poured it not upon the ground" (1769) View online

Ezekiel 48:8

"which they shall" (1611) View online

"which ye shall" (1769) View online

Daniel 3:15

"a fierie furnace" (1611) View online

"a burning fiery furnace" (1769) View online

Matthew 14:9

"the othes sake" (1611) View online

"the oath's sake" (1769) View online

1 Corinthians 12:28

"helpes in gouernmets" (1611) View online

"helps, governments" (1769) View online

1 Corinthians 15:6

"And that" (1611) View online

"After that" (1769) View online

1 John 5:12

"the Sonne, hath" (1611) View online

"the Son of God hath" (1769) View online

Profanity

What about the profanity in the KJV found in: 2 Peter 2:16, 2 Kings 9:8, 1 Samuel 25:34, etc...

False Friends

One argument occasionally advanced is that the NKJV ought not to be used because it purportedly alters “key” theological terms. For example, some have claimed that forms of the word save (salvation) occur less frequently in the NKJV than in the KJV, thereby suggesting that the NKJV modifies the text in ways that diminish or obscure doctrines related to salvation. Such assertions, however, are misleading. They typically fail to account for historical shifts in English usage, differences in lexical range, or the fact that the underlying Greek and Hebrew texts remain unchanged. Consequently, claims of this nature amount to a distortion of the evidence rather than a legitimate textual concern.

The term saved in 1611 possessed a considerably broader semantic range than it does in contemporary English. Among its historical uses was the sense “except,” a meaning no longer familiar to most modern readers. For example, consider Matthew 13:57:

"A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country, and in his own house." (KJV)

“A prophet is not without honor except in his own country and in his own house.” (NKJV)

Is this a salvation or an archaic word usage issue? The claim in question has become increasingly rare, in large part because of the attention drawn to “false friends” in the KJV through the work of Mark Ward. A “false friend” denotes a term that remains in contemporary English but whose semantic range has shifted—sometimes partially, sometimes entirely—from its meaning in an earlier stage of the language. Such shifts readily lead to misunderstanding, as modern readers naturally import present-day meanings into a historical text without recognizing the broader or different lexical range the word possessed at the time of its original usage.

I would encourage you to view

Mark Ward’s “False Friends” series on YouTube, in which he systematically highlights terms in the KJV that remain in contemporary English but carried different meanings in 1611.

A helpful entry point is his video titled

“KJV Words You Don’t Know You Don’t Know.”

Unusual Translational Choices

The KJV also includes several unusual translational choices. For example, in Acts 12:4 the translators render pascha (πάσχα) as “Easter,” even though every other occurrence of pascha in the New Testament is correctly translated by the KJV as “Passover,” as in Matthew 26:2. This inconsistency does not arise from any variation in the underlying manuscripts; rather, it reflects a translational decision shaped by the linguistic and ecclesiastical context of early seventeenth-century England.

This is why, in Acts 12:4, the AMP, CSB, NASB, NET, NIV, NKJV, NLT, ESV, et. al. render the Greek pascha (πάσχα) as “Passover.” It is historically implausible to suppose that Luke intended to refer to the later Christian holiday of Easter. The term simply did not carry that meaning in the first century.

KJV Paralell Bible

Mark Ward has also produced a KJV Parallel Bible designed to illustrate the minimal differences between the Critical Text and Scrivener’s Textus Receptus—the latter being the Greek text underlying the King James Version. In this resource, Ward presents how the KJV would read if its translators had been working from the Critical Text rather than the TR. The comparison makes clear that many perceived discrepancies between the KJV and modern translations stem not from substantive textual divergence but from differences in translation philosophy and, above all, from the semantic shift of English over the past four centuries. In many cases, what readers believe the KJV is saying is not, in fact, what the text conveyed to its original seventeenth-century audience.

You may view the parallel Bible here:

KJVParallelBible.com

Which TR?

If the TR (Textus Receptus) Greek New Testament is perfect, which one are you referring to? The one created by Stephanus in 1550, or the one created by Erasmus?

Luke 2:22

"their purification" καθαρισμοῦ αὐτῶν (NA)

"their purification" καθαρισμοῦ αὐτῶν (Erasmus TR)

"their purification" καθαρισμοῦ αὐτῶν (Stephanus TR)

"their purification" (NASB)

"her purification" καθαρισμοῦ αὐτῆς (Scrivener's TR 1894)

"her purification" (KJV)

Luke 17:36

Omits the passage (NA)

Omits the passage (Erasmus TR)

Omits the passage (Stephanus TR)

Has this passage (Scrivener's TR 1894)

Revelation 22:2

Erasmus had ξύλου τῆς ζωῆς (“tree of life”) and Stephanus had βίβλου τῆς ζωῆς ("Book of Life"). The Stephanus reading was adopted by the KJV.

Greek Manuscript Corrections

Papyrologist Young Kyu Kim gives the earliest date for P46 as the first century. He bases this date off handwriting and archaic spelling. Kim states that P46 “reserves the εγ- [

eg] form instead of the εκ- [

ek] before compounds with β [

b], δ [

d], and λ [

l].” Kim offers twelve examples of this. This feature is extremely rare even among the older extant New Testament papyri.

In Hebrews 12:3 P46 has εγλελυμενοι (

egl) but P13 has εκλελυμενοι (

ekl). In Hebrews 12:5, P46 has εγλελησθε (

egl) and P13 has εκλελησθε (

ekl), although both have εγλυου (

egl) in this verse. P13 is dated to 225-250 A.D.

This example illustrates that virtually all manuscript traditions have undergone orthographic correction, as occurred with P13. Although one instance preserves the archaic spelling, the remaining two were revised to the later form. Similarly, manuscripts produced after the second century consistently standardize the spelling. It is highly improbable that a scribe would deliberately “archaize” a text. The presence of ἐγλύου in both P46 and P13 confirms this: had a scribe intentionally altered the form to create an archaic appearance, we would expect all three occurrences to exhibit the same spelling rather than a mixture of corrected and uncorrected forms.

Young Kyu Kim article can be viewed here.

Modern Versions are Copyrighted

Some have claimed that the KJV is superior to modern translations on the grounds that modern versions are copyrighted. Yet the KJV itself is also under copyright protection. Indeed, its situation is arguably more restrictive: whereas modern copyrights expire after a defined period, the KJV enjoys a perpetual royal copyright in the United Kingdom. As Michael Gove laments:

The crown has a perpetual copyright on the King James Bible, through "letters patent" originally issued to stop unofficial editions and then to protect the country from ranters, shakers, Quakers, nonconformity and popery. Thus today we can't freely reprint, circulate passages, write commentaries and draw upon the text in the way we might with other texts of the time, such as Shakespeare's plays. Bizarrely, these restrictions only apply in the UK. (Source

theguardian.com)

Ironically, even KJV-Only advocate Peter Ruckman secured a copyright for his 1980 book. I wonder why?